President of Sri Lanka Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s three-day state visit to India was characterised by exceptional warmth and a welcoming atmosphere. The numerous meetings, a diverse range of topics discussed, and MoUs established during the visit reflect renewed vigour and energy in the bilateral relationship, writes Ivor Vaz.

Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s recently concluded three-day state visit to India (December 15-17, 2024) marks a significant milestone in the evolving relationship between the two neighbouring countries. His first official overseas trip since assuming office in September 2024 adheres to tradition and signifies continuity in India-Sri Lanka bilateral relations. The visit underscores a clear commitment to enhancing economic ties with India while addressing ongoing concerns about China’s influence in Sri Lanka. This is also Dissanayake’s first visit to India, which comes in the wake of the recently concluded presidential and parliamentary elections in Sri Lanka, amid a gradual recovery from the country’s economic crisis.

PM Narendra Modi presents a token of appreciation to the President of Sri Lanka,

Anura Kumara Dissayanake, at Hyderabad House, New Delhi

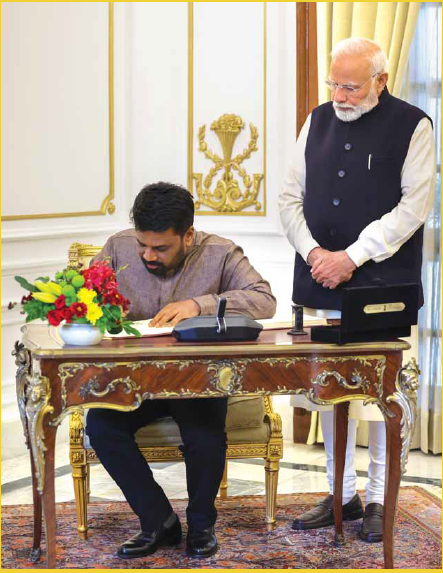

President of Sri Lanka Anura Kumara Dissayanake and PM Narendra Modi sign the joint agreement

Undertaken at the invitation of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the visit reflects Sri Lanka’s pivotal position in New Delhi’s ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy, given its 2,500-year-old civilisational ties, strategic location, and significant role in India’s regional initiatives. The choice of India as the destination for the new government’s first presidential visit highlights mutual trust, friendship, and strategic interdependence.

Earlier this year, India’s External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar and National Security Adviser Ajit Doval visited Sri Lanka to participate in the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Colombo Security Conclave, respectively. Notably, Jaishankar’s visit marked the first diplomatic engagement by a foreign dignitary following Dissanayake’s assumption of office in September 2024.

During his meeting with PM Modi, Dissanayake expressed gratitude for India’s role in stabilising Sri Lanka’s economy during its collapse in 2022. He reiterated his vision for economic cooperation that prioritises sustainable development and recovery.

The visit culminated in a joint statement outlining various collaborative initiatives, from energy partnerships to regional security cooperation. India’s decision to supply liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Sri Lanka and partner in renewable energy projects reflects its ongoing commitment to help Sri Lanka diversify its energy sources. A major announcement was the agreement to build an energy pipeline connecting the two countries, a project involving the United Arab Emirates. This pipeline, alongside plans to establish Trincomalee as a regional energy hub, highlights India’s strategic interest in deepening its influence in the Indian Ocean region while addressing Sri Lanka’s critical energy needs.

Additionally, both countries emphasised the importance of resuming passenger ferry services and rehabilitating key infrastructure projects, such as the Kankesanthurai port, to enhance connectivity. India’s continued involvement in developing housing, transportation, and digital infrastructure aligns with its ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) initiative.

Balancing Opportunities and Challenges

While the agreements and announcements signal opportunities for economic recovery and stronger bilateral ties, concerns remain regarding their long-term implications for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and economic independence. Criticism has emerged domestically, most notably from the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), a breakaway faction of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), which forms the core of the ruling National People’s Power coalition. The FSP has argued that these deals could disproportionately favour India while undermining Sri Lanka’s local workforce, resources, and autonomy. Such criticisms could impede the forward momentum of the Dissanayake administration, whose party had often criticised former President Ranil Wickremesinghe for his dealings with India.

In a statement, the FSP specifically raised alarms over the proposed development of Trincomalee into an Indian economic hub, which could displace over 7,000 families. The allocation of large tracts of land to foreign projects and the prospect of resource exploration rights being handed to Indian entities in regions like Mannar and Kuchchaveli have heightened fears that Sri Lanka’s natural wealth could be exploited at the expense of its people.

Another significant concern stems from the revival of the Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement (ETCA), which Dissanayake had previously criticised. The FSP argued that ETCA’s provisions for liberalising trade in services could open Sri Lanka’s job market to an influx of Indian professionals, potentially displacing local workers. Critics warned that this could affect highly trained professionals and small-scale workers in industries like transportation, barbering, and street vending, as cheaper labour from India could overwhelm local job markets.

The energy sector, another key focus of the visit, also drew scrutiny. While India’s involvement in LNG supply, offshore wind power, and power grid interconnection could help address Sri Lanka’s immediate energy needs, critics argue that such partnerships could make Sri Lanka increasingly dependent on Indian energy infrastructure. The FSP highlighted Bangladesh’s experience with India, where energy agreements granted significant control to Indian conglomerates like the Adani Group, effectively reducing Bangladesh’s energy sovereignty. Similar fears are echoed in Sri Lanka, particularly as energy partnerships often lack transparency regarding long-term costs and benefits.

Geopolitical Considerations

These criticisms are further tied to broader geopolitical concerns. The FSP’s Wasantha Mudalige pointed to India’s long-term vision for regional dominance, citing the ‘Akhand Bharat’ concept, which imagines a unified South Asia under Indian influence. According to Mudalige, India’s increasing economic and strategic role in Sri Lanka could lead to an erosion of political autonomy, reducing Sri Lanka to a satellite state. Such sentiments reflect deep-seated anxieties within Sri Lankan society about maintaining national sovereignty while pursuing external partnerships.

Despite these concerns, Dissanayake’s visit also reflects a pragmatic approach to rebuilding the country’s economy following the devastating collapse of 2022. India’s financial support, which included $4 billion in aid for food, fuel, and medicines, played a crucial role in stabilising Sri Lanka’s economy during its most challenging period. The agreements reached during Dissanayake’s first presidential visit to New Delhi aim to build on that foundation by encouraging investment-led partnerships, improving connectivity, and enhancing trade. India’s plan to promote INR-LKR trade settlements could provide much-needed relief to Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves, while proposed capacity-building programs, such as training 1,500 civil servants over the next five years, represent efforts to strengthen local governance structures.

Balancing the benefits of these initiatives with the risks they pose remains a challenge for Dissanayake’s government. Critics argue that Sri Lanka must approach these partnerships cautiously to ensure they align with the interests and aspirations of its people. While collaboration with India offers economic opportunities, transparency, equitable resource sharing, and protection of domestic industries must remain priorities. Dissanayake’s leadership will be tested in navigating these agreements to foster recovery without compromising Sri Lanka’s sovereignty or local livelihoods.

The visit has undoubtedly set the stage for a new chapter in bilateral relations. Its success will depend on how these agreements are implemented and whether they truly benefit Sri Lanka’s people. As the country strives to rebuild, Dissanayake’s government must strike a careful balance — leveraging India’s support while safeguarding Sri Lanka’s independence, economy, and long-term stability.