The RCEP, India most-ambitious trade pact, is currently under negotiation. It includes the 10-nation bloc of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and their six free-trade partners — China, India, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. The countries working towards finalizing RCEP comprise a quarter of global gross domestic product, 30% of global trade, 26% of foreign direct investment flows, and 45% of the world’s population.

“Engagement with ASEAN is at the core of India’s ‘Act East’ policy. ASEAN is the gateway to the Indian Ocean region and as close partners, there is convergence of views in India’s and ASEAN’s outlook in the region,”.

India’s bilateral trade jumped threefold from $21 billion in 2005-06 to $96.7 billion in 2018-19. ASEAN countries together have emerged as the largest trading partner of India in 2018-19 (followed by the US), with a share of 11.47 per cent in India’s overall trade, while India was ASEAN’s sixth largest trading partner in 2018.

Investment flows are also substantial both ways. The foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into India from ASEAN in the April-March 2018- 19 period was about $16.41 billion which is approximately 36.98 per cent of total FDI flow into India.FDI inflows from India to ASEAN in 2018 was $1.7 billion, placing India as ASEAN’s sixth largest source of FDI.

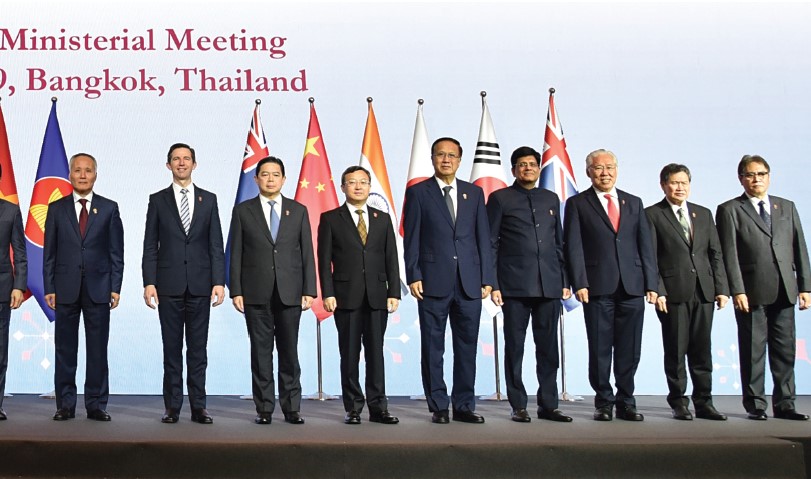

Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal is representing India at the Trade Ministers’ meeting of member countries of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Bangkok and the East Asia Economic Ministers Summit in Bangkok between September 8-10.The Minister is also scheduled to hold bilateral meetings with his counterparts from Japan, Singapore, China, Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Russia, according to an official release.“The meetings will be attended by Economic Ministers and senior leaders of the 10 ASEAN member countries and eight East Asia Summit (EAS) countries,” according to an official release.The Trade

Ministers of RCEP countries, which includes the 10-member ASEAN, India, China, South Korea, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, will try to give a final shape to the proposed free trade pact which includes several areas such as goods, services, investments, intellectual property and government procurement.

Twenty-eight rounds of talks have concluded, apart from eight ministerlevel meetings.The RCEP meet in Bangkok this month is aimed at closing a mega trade deal that has been in the works since 2012. The Bangkok meet this month hopes to narrow differences in the deal that has been in the making since 2012.

India’s Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal did not attend a ministerial meet in China last month against the backdrop of Indian concerns of cheaper imports from China overwhelming India’s manufacturing sector, if India joins the grouping. India’s trade deficit with China in 2018 was more than $60 billion.Representatives of iron and steel, dairy, textiles, marine products, electronics, chemicals, pharmaceuticals and plastic industries have been the most vocal against the trade deal.There is a general feeling that India’s trade agreements have not worked out well.

The first point of objection with the RCEP is that India’s trade deficits have always widened with nations after signing free-trade-agreements (FTAs) with them. The same is true for India’s FTAs with the ASEAN, Japan, Korea, and Singapore, most of which are RCEP nations. So far, the rise in Indian trade deficit with its FTA partners has occurred due to cheap imports of final products that have led to an increase in consumer surplus (or consumer well-being), but adding to the angst of the domestic producers.

The second point of contention lies with exposing vulnerable sectors to market forces and the vagaries of competition emerging from global trade. Even after more than quarter of a century of economic reforms, Indian manufacturing are yet to mature to be competitive enough to face the vagaries of competition brought about by international trade.

Under such circumstances, the Indian industry is hardly in a position to compete in a level playing ground in a free-trade region. “Make in India” is meant to create enabling conditions for both domestic and foreign businesses to thrive. If domestic industry has to thrive,

it needs protection as also the enabling conditions created by factor and product market reforms. Megatrade deals like the RCEP may derail the timing and coordination of such plans.

The country is also not in any mega trade pact that includes China, which is a part of RCEP. There is concern that Chinese imports will become a bigger problem if a deal is signed. Aware of its massive trade deficit, India is preparing a final list of products on which it may retain import tariffs for China in the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, said official sources.

The government has been preparing such a list for a while now, based on its plan of a “differential tariff reduction”. China, which has benefited the least, has opposed this move, along with richer economies such as Australia and New Zealand.“Considering our sensitivity to imports from China, this has been the case throughout,” said a senior government official, who did not want to be named, adding: “An extensive list is being prepared.”He also said the list was unfinished and was being drawn up after extensive consultation with domestic industry.

Sources also said India had suggested a mechanism to fix an import ceiling, again particularly for China. This is the first time New Delhi will fix such a ceiling in any trade deal. Government officials did not confirm this, but they said similar proposals had been opposed by other nations before. Earlier, India had agreed to reduce tariffs on 76 per cent of all items for all nations, apart from special measures for China. Others had demanded New Delhi open up at least 90 per cent of all items.

Currently, it is broadly accepted the RCEP will lead to tariffs being eliminated on 28 per cent of the traded goods to begin with. This will be followed by 35 per cent of all products being eliminated in phases.

Officials also said the final deal would necessarily include all negotiating countries. India had been on the receiving end of repeated questions by other nations on whether it is serious about signing the deal. Senior leaders of Asean, including Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Bin Mohamad, had said the mega Asia-Pacific deal could be negotiated without India “for the time being”. Senior diplomatic sources of other nations confirmed that commitments to reduce tariffs were now dependent on individual nations. This may result in each nation setting a specific tariff reduction for each of the rest.

The government has also dismissed the idea of an “early harvest” approach to the RCEP talks. If this approach was adopted, it would mean the agreement would be signed after some issues had been agreed upon, while others would be resolved eventually.

The current stance is a shift from India’s earlier position of adopting a “package of early deliverables” created by the trade-negotiating committee of the RCEP. Australia’s lead trade negotiator James Baxter has said the last ministerial meet in Bangkok saw all negotiating trade ministers unanimously decided to complete the negotiations in full by November, seven years after the talks started.

“As long as India’s domestic industry and our national interests is protected, the faster it (RCEP) is done, the better it is for India,” Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal, has said.